For patients

Deep venous disease

Blood clots in the veins are known as deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and can travel to the lungs, becoming a pulmonary embolism (PE). Learn more about the signs, symptoms and risk factors that contribute to blood clot development.

Signs and symptoms

What is deep venous disease?

When the flow of blood in blood vessels changes or the clotting system of the blood vessels is abnormal, a blood clot can form. Blood clots in the veins are known as deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and can travel to the lungs, becoming a pulmonary embolism (PE).

Deep vein thrombosis: Deep vein thrombosis can occur in any vein in your body, but most commonly DVT forms in the legs. A leg DVT can be in a small vein or can span the entire leg. This can lead to swelling, pain and color changes of the leg.

Pulmonary embolism: When pulmonary embolism occurs, it is usually small enough so that blood can flow around the clot and into the lungs. However, in some cases, the clot can be large enough to block much of the blood flow to the lungs. In severe cases, this can lead to heart failure and/or death.

Together, DVT and PE are called venous thromboembolism (VTE). VTE can be life threatening.

What are the symptoms of a deep venous blood clot?

Common symptoms for DVT include:

- Swelling, pain and tenderness in the limb

- A tired, heavy feeling in the limb

- Abnormal coloring

- Surface veins becoming more visible.

Common symptoms for PE include:

- Shortness of breath

- Pain when taking a deep breath

- Cough, sometimes bloody or with a frothy pink quality

- Increased heart rate

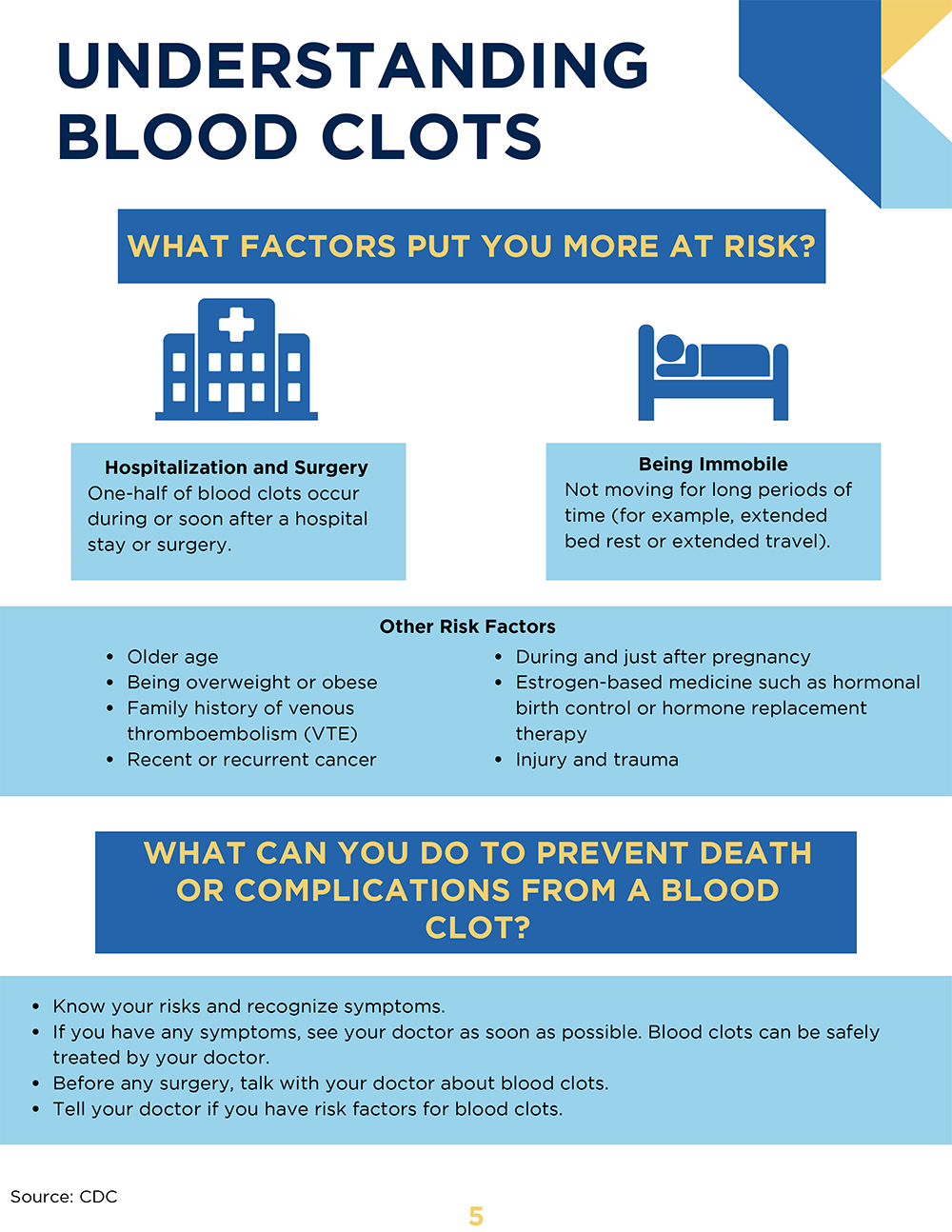

Who is at risk?

You are at increased risk of DVT if you have:

- been immobilized for long periods (bed rest, hospitalization and long plane flights)

- had recent surgery, recent trauma or injury (such as a bone break or muscle tear), cancer, current infection, a history of previous DVT

- a family history of DVT

Certain medications, including oral contraceptives or other hormone treatments, and a current or recent pregnancy also increase your risk of blood clots.

Excessive weight or obesity and smoking can also increase your risk of developing a blood clot.

Are there other forms of deep venous disease?

Chronic venous insufficiency

Chronic venous insufficiency describes the disorder of veins preventing the backflow of blood back to the heart, which commonly leads to pooling of blood in the legs.

May–Thurner syndrome

When the right iliac artery (the main blood vessel for the right leg) rests on top of the left iliac vein (the main vein draining the left leg in the pelvis), causing pressure, the result is named May–Thurner syndrome. This pressure on the left iliac vein can cause blood to flow abnormally, which can have serious consequences. May–Thurner syndrome is also known as iliac vein compression syndrome, iliocaval compression syndrome or Cockett syndrome.

Outside of interventional radiology, May–Thurner syndrome can be difficult to diagnose, but it should be considered as it has been shown to increase the likelihood of developing DVT in addition to other symptoms, such as pelvic pain, that can result from pelvic vein dilation.

Learn more about the signs, symptoms and risk factors that contribute to blood clot development.

Minimally invasive options

How is venous thromboembolism diagnosed?

Venous thromboembolism can be life threatening. If you suspect that you may have DVT or PE, you should notify your healthcare provider or go to the emergency room as soon as possible. Part of the evaluation will include an ultrasound of your leg veins. A specialized CT and/or another scan of your lungs can be performed. Once DVT and/or PE is found, an interventional radiologist may be able to perform minimally invasive, image-guided treatment to remove those clots.

How do IRs treat deep venous disease?

Blood-thinning medication: The main treatment for VTE is blood-thinning medication. Blood thinners are given to stop new clots from forming. In patients who cannot receive blood thinners, have additional clot formation despite blood-thinning medication or have a particularly large amount of clotting, an interventional radiologist may place a filtering device in the affected vessel or perform an interventional treatment described below.

Interventional treatment of deep vein thrombosis: With each treatment, an interventional radiologist makes a small incision to access the femoral vein (the large vein in the thigh). Guided by X-rays, the doctor inserts a catheter (a thin plastic tube) through the vein to the DVT (clot) site.

Thrombolysis

Using imaging guidance, IRs place specialized catheters within a blood clot. These catheters will allow clot-melting medication, called tissue plasminogen activator (TPA), to be injected directly into the clot. This allows for complete treatment of the blood clot over 1–2 days. During this treatment, people are often placed in the intensive care unit (ICU) for closer monitoring. In some cases, this can be offered in combination with mechanical thrombectomy, a procedure to remove the clot.

Mechanical thrombectomy

With mechanical thrombectomy, the interventional radiologist guides a device through the veins to the DVT site. Once there, the doctor uses the devices that are available to remove the clot. Occasionally, the clot needs to be broken up into smaller pieces to allow for removal.

Angioplasty and stenting

After treating the blood clot, the interventional radiologist may find a stenosis, which is a narrowing in the vein that limits blood flow. The stenosis can be treated by angioplasty, where inflating a balloon makes the vein larger. In some situations, a metal tube called a stent may need to be placed as a scaffold to widen the vein, propping the vein open to allow blood flow and prevent the vein from narrowing again.

Inferior vena cava filter (IVC filter)

For people who cannot tolerate other treatments, a filtering device may be placed within the inferior vena cava (IVC), the large vein in the abdomen that drains the blood from the legs. The IVC filter acts like a small net, allowing for normal blood flow, but catching any traveling blood clots, preventing a DVT from moving to the lungs. Additionally, most IVC filters will be removed once the blood clot has cleared or when you can begin taking blood thinners to treat the clot.

Follow-up and recovery

Life after treatment

What is the treatment’s recovery like?

Because many of these treatments are performed in emergency situations, you may have to stay in the hospital for observation to ensure additional clots do not form or travel to the lung causing pulmonary embolism. However, due to the minimally invasive nature of the treatments performed by an interventional radiologist, the recovery time for the procedure is normally very short. Once you are released from the hospital, you can resume normal activity if cleared by your doctor.

Your interventional radiologist will likely prescribe blood thinners to prevent more clots from forming after treatment. Additionally, you may be advised to wear compression stockings to help manage leg swelling.

During your follow-up appointments, your interventional radiologist will evaluate your progress and address any remaining issues or symptoms that you may have. If your treatment included an IVC filter, your IR will develop a care plan to ensure that the filter is removed at the appropriate time once the clots have cleared.

What are the risks of the treatments?

For patients who received blood thinners, there is a risk of excessive bleeding or clotting if your blood is not kept at the correct consistency. Your physician will monitor the thickness of your blood to ensure that it is within an appropriate range for you to avoid these side effects.

For patients who received IVC filters, there is a small risk that the filter can travel if it is left in place for too long. This is why it is part of the care plan to retrieve the filter after the clot has dissolved and the filter is no longer needed.

As with any treatment that involves puncture to the skin, there is a small risk of infection at the site of treatment.

Use SIR's Doctor Finder to search for interventional radiologists in the United States and abroad.

Reviewed by the Venous Clinical Specialty Council. September 2024.